Table of Contents

Q&A: /u/AndreLeo and Their Home Cultivated Bioluminescent Fungus

Mycelium connected with /u/AndreLeo from Reddit after learning about some of their interesting DIY mycology projects. Learn about bioluminescent fungus in our interview!

Interview with /u/AndreLeo

Can you start by telling me about yourself?

/u/AndreLeo: So, I am a Chem undergrad from Germany. I’ve been interested in MINT/STEM topics all my life, basically covering everything from quantum mechanics - not claiming to be good at it - to insects and, of course, fungi.

My main interests are specifically mycology, microbiology, myrmecology (study of ants), and electrochemistry. I got interested in mycology because doing chemistry at home all the time can be rather dangerous and frustrating. Before you ask, yeah, I have managed to almost blow myself up a couple of times. Fortunately, my safety standards have improved quite a bit over the years.

Which species of bioluminescent fungus did you choose?

/u/AndreLeo: Well, I didn’t choose a bioluminescent fungus species in particular. Generally speaking, I’m absolutely obsessed with bioluminescence, and I look for any species I can get.

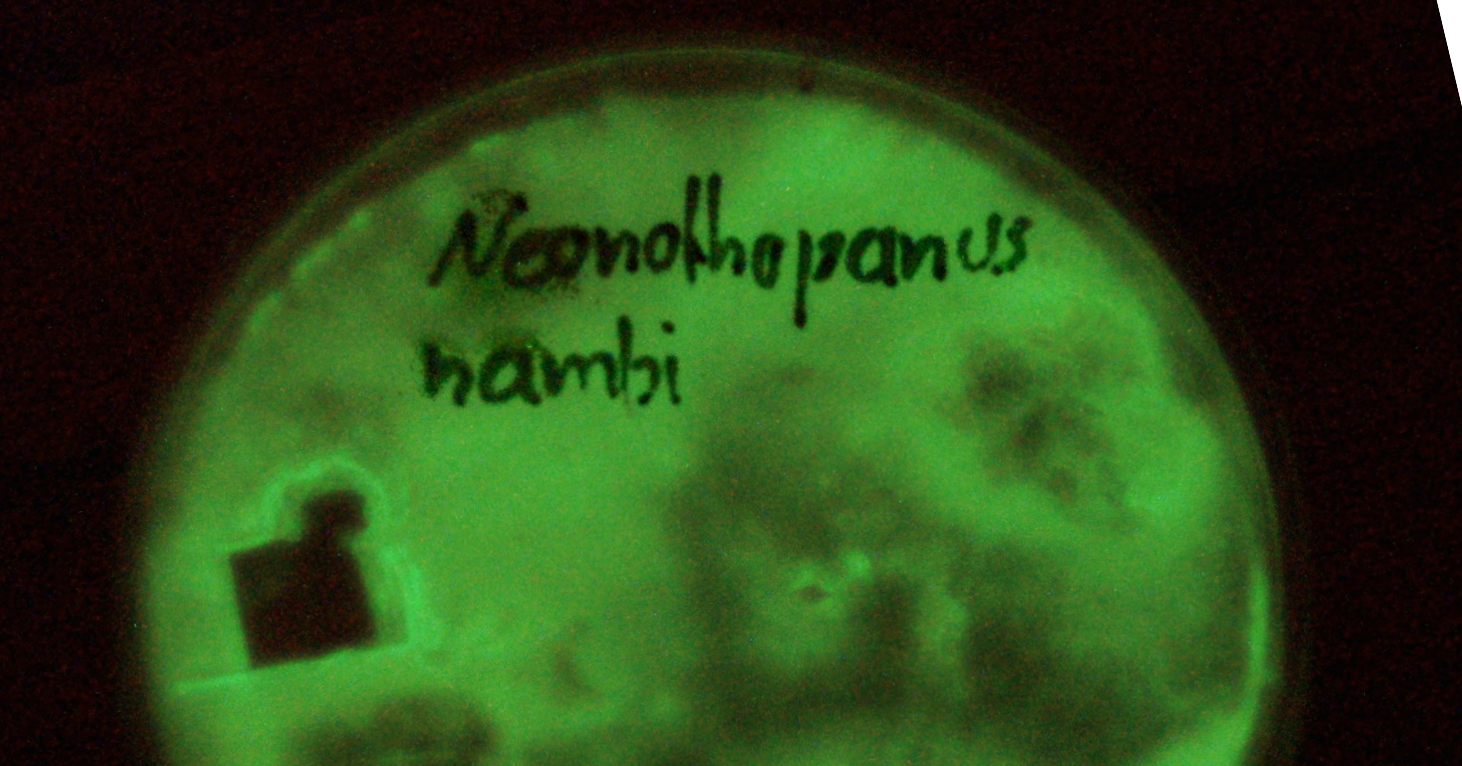

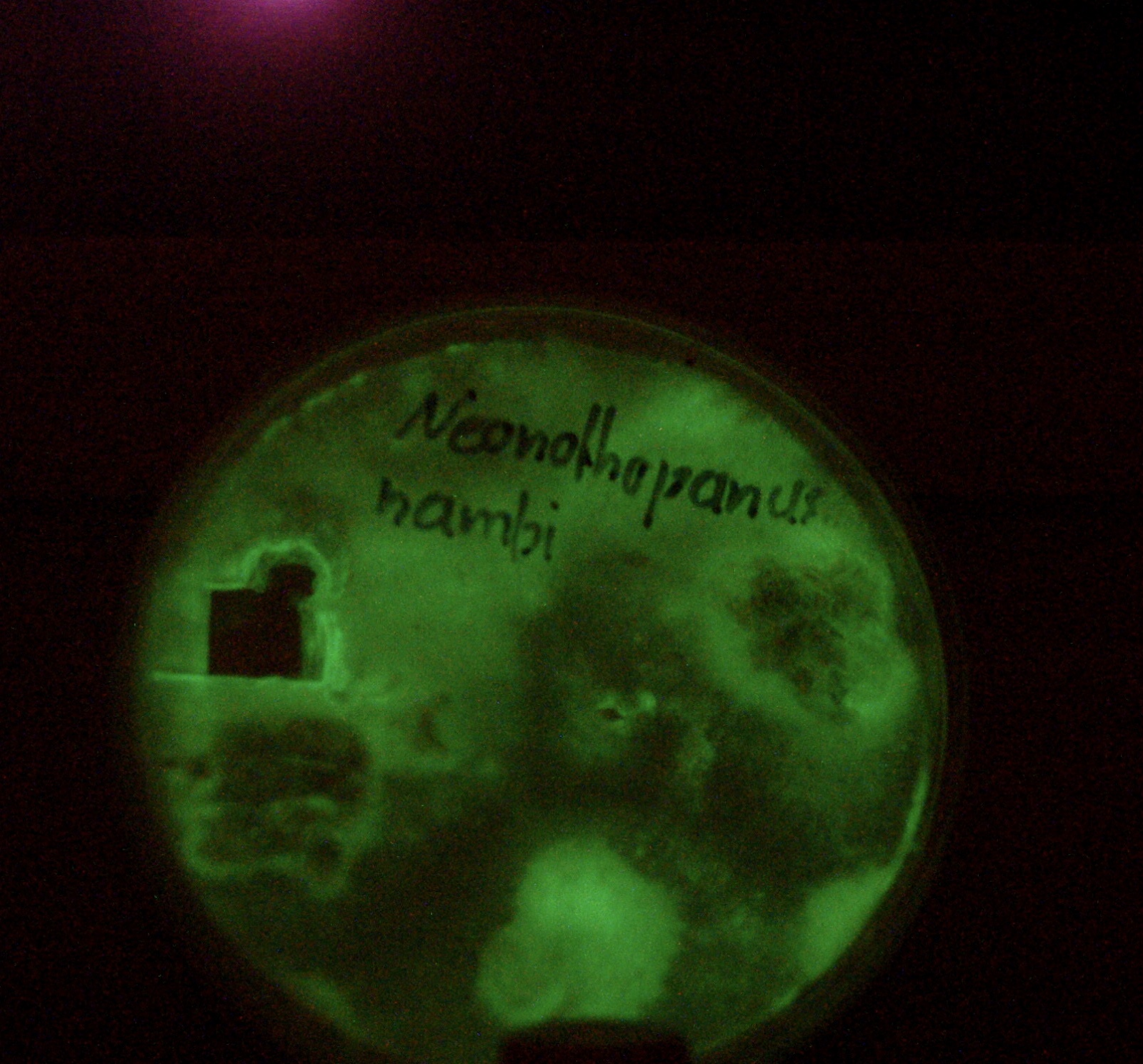

My main focus so far is Panellus stipticus (also known as bitter oyster) and Neonothopanus nambi, which is a close relative of N. gardneri (known by locals as “flor de coco,” literally translating to “coconut flower”). The infamous “living nightlight” was rediscovered several years ago in Brazil (2005).

Other than the two species already mentioned, I got my hands on Omphalotus nidiformis, also known as “ghost fungus” and Armillaria cepistipes spores.

Can you tell me a little bit more about that species?

Due to being rather proud of myself for getting Neonothopanus nambi after so many years of patiently waiting, I’ll stick with that even though information regarding the species is rather sparse, to say the least.

It seems to be distributed in wide areas of Brazil and Asia. The molecular mechanism that creates the fungus’ bioluminescence has been subject to intense research. The molecular mechanism is based on a caffeic acid derivative known as 3-hydroxy hispidin reacting with an enzyme, a fungal luciferase, and oxygen to yield a photon and oxyluciferin. The mechanism is quite hard to explain without getting into too many details.

In 2018 researchers were able to insert the fungus genes into yeast to make it glow! Maybe we’ll see glowing beer or glowing bread very soon - at least I hope we will because that would be awesome. Those genes have even gotten inserted into tobacco plants, so I’d say the researchers are definitely up to something here! How / why did you choose it?

My basic procedure to acquire bioluminescent fungi is mainly waiting until some dude on the internet finally shows up selling a species that I am desperately looking for. It’s maybe not the most effective method, but it has proven to be the most reliable so far.

I have contacted dozens of researchers in hopes of somehow getting a culture of Mycena chlorophos or Neonothopanus gardneri, which are both said to be among the brightest species known - they’re allegedly even bright enough to read by, but so far no success.

One could imagine how hyped I was to find a local vendor on Etsy selling a species that I had spent five years looking for. I hoped this species of mycelium would glow brighter than that of the commonly sold bitter oyster. This is somewhat true as bioluminescence seems to greatly depend on air pressure and temperature. Some days, at least, the nambi is brighter, but so far I haven’t gotten the bitter oyster to fruit, so I don’t have any references.

What are the steps involved with growing bioluminescent fungus?

The basic procedure of growing bioluminescent mushrooms is very much the same as it is for any other wood-decaying species out there. However, due to the extremely slow growth of bioluminescent species, grain spawn has shown ineffective as it tends to get moldy because every spore has enough time to spread inside the jar, even though the myc is dominant enough to just overgrow the mold. The jars tend to turn into a nasty mess.

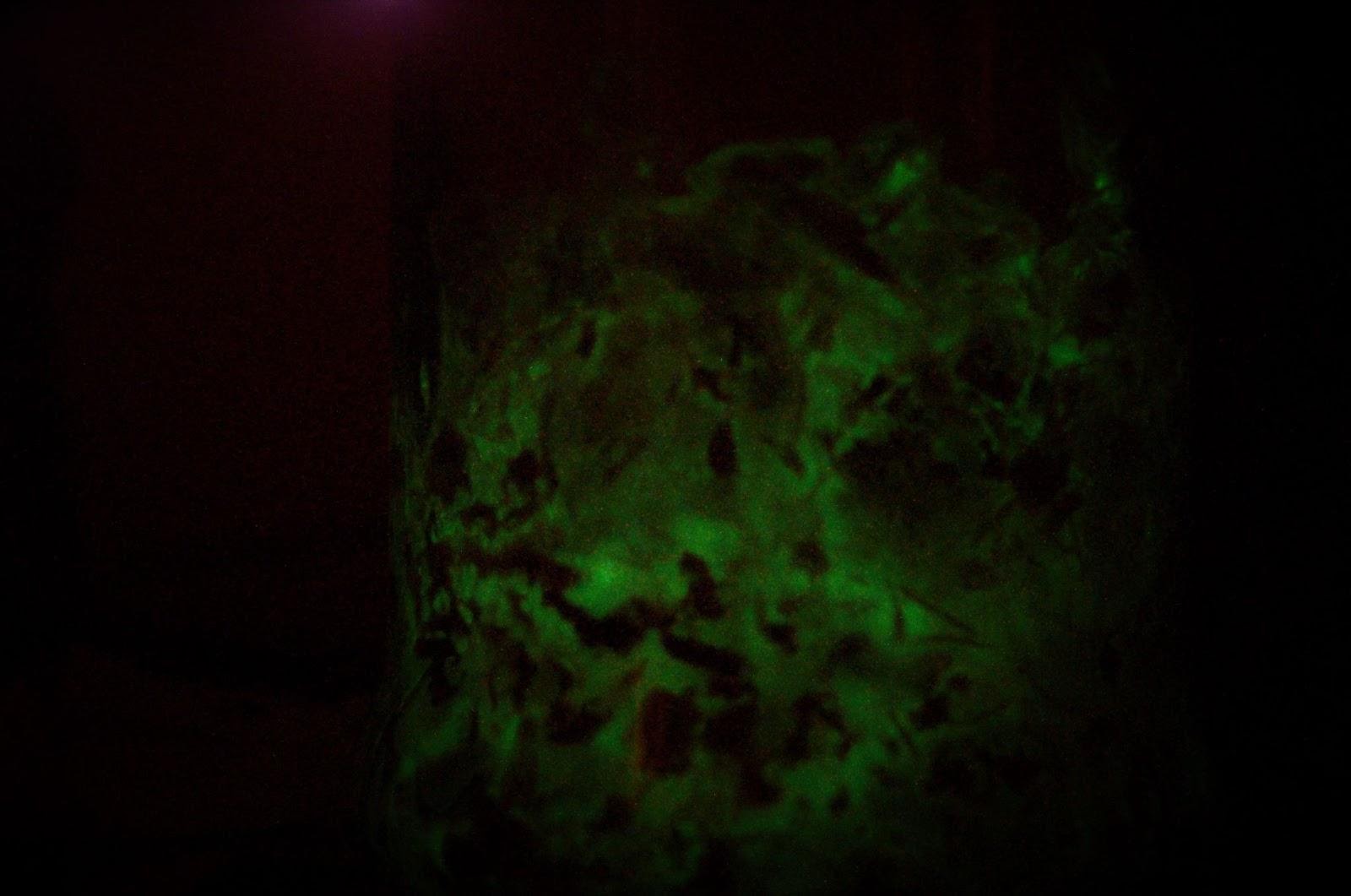

Colonizing a jar takes about six weeks for both nambi and stipticus. The method I prefer to stick with is to either completely sterilize a substrate, which consists of 75:25 hardwood chips to oat flakes, inoculating this mix directly with agar, and transferring it to a bulk substrate after four to six weeks.

Alternatively, you can use mycelium dowels to inoculate a log and forget about it for half a year (which is usually the time both species need to begin fruiting). Unlike most other species, these don’t seem to induce pinning by either direct sunlight or cold temperatures. Trust me, I’ve tried everything. So, much to my surprise, I found a four-to-six-week-old plate slowly start to show pins - maybe there were several sub-strains in my culture, one of which easily starts fruiting. That calls for cloning them once they have fully developed, or at least as far as the remaining nutrients allow.

What equipment do you use?

- A pressure cooker

- A still air box

- A Nikon d50 camera for the photos

- Standard stuff for mycology - ranging from glass labware and magnetic stirrer to petri dishes

How long does it take to grow bioluminescent fungus?

From mycelium to mushrooms, I’d say around six to seven months, but it’s worth it! The caps will usually stay for several weeks before ceasing, and a good hardwood substrate can even produce caps for several years. This would maybe even be a nice addition to a tropical terrarium.

To sum it up for Neonothopanus nambi:

Petri dishes usually take three weeks to a month until the mycelium has thoroughly grown The oat flake-hardwood substrate takes around six weeks The hardwood fruiting block takes at least another three to four months until it’s ready for fruiting

Is there anything special about growing this fungus that other people might want to know before they try?

Bioluminescence in both nambi and stipticus is highly nitrogen and pH- dependent. If you want to have optimum bioluminescence, use an acid buffer to adjust the pH between 3.5 and 4, approximately. At pH 6-7, no bioluminescence can be seen, so keep that in mind if you decide to try grain spawn.

Also, the addition of a bit of yeast extract boosts bioluminescence in the nambi. Hardwood usually has a low pH, so it should produce visible light. Keep in mind the bioluminescent fungi commonly sold only produce very dim bioluminescence, so you should take your time and let your eyes adapt to complete darkness (which takes around 5-10 minutes). How do you photograph bioluminescent fungus?

If you hope to photograph bioluminescent mycelium with your phone camera, just forget about that, it won’t work. Trust me, I have tried.

What you want to use instead is a proper DSLR camera that is capable of a 2-5 minute exposure at an ISO of 1600. Preferably you have a camera with bulb mode, which means the exposure is as long as you hold the trigger. It’s best to use a remote shutter for your camera. Also, the aperture should be at least f/5, which means you may need image stacking for proper depth resolution.

Can you share any photos of your process?

Yes, here ya go:

Can you share a photo of the final product?

Unfortunately, no. I’m still working on better-quality pictures. The nambi is the only one beginning to show pins.

Do you have any plans to grow other bioluminescent fungi?

Yes, definitely! I’m looking forward to eventually getting both Neonothopanus gardneri and Mycena chlorophos. Maybe I’ll find someone willing to take samples or do a spore print for me. My ultimate goal is to be able to read by the mushrooms, and less realistically, transform my bedroom into some avatar-like landscape. Come to think of it, maybe that’s not impossible as I’ve already got bioluminescent fungi, algae (specifically dinoflagellates), bacteria (definitely bright enough to read by), as well as bioluminescent click beetle larvae from whom my wallet is still bleeding. Do you have any other projects you want to tell people about?

Yes, I have several ongoing personal projects. One focuses on producing a leather-like material from fungi and bacterial cellulose; the latter is produced by a bacteria strain commonly found in SCOBY. Even though the project so far shows promising results, I need to work on the color and texture. It has a deeply unsettling similarity to leather produced from human skin, but it’s a very tough material. The main problem has been finding a non-toxic, biodegradable softener that is chemically linked to the material so it won’t wash out when it’s used for clothing or such.

Another one of my projects involves getting bioluminescent bacteria to glow bright enough to weakly illuminate a whole room so much so that you can read by their glow. Unfortunately, those use up the nutrients inside the agar within about two days. An interesting finding is that you can use the bioluminescent bacteria to make Artemia salina - the sea monkeys we all had growing up - glow.